After 60 years without a raise, Boston cops went on strike

Beginning around 10 p.m. on Sept. 8, 1919, members of the new Boston patrolmen's union started voting on whether to go on strike the next day.

The police commissioner had rejected their requests for raises and better working conditions - they had to work upwards of 80 hours a week and had not seen a weekly pay increase in six decades - the governor had refused to accept a fact-finding commission's recommendation that urged improvements and the mayor, well, it didn't matter much what the mayor thought since the Brahmins that ran the state had taken away Boston's direct control of the police department back in the 1880s, after voters elected the city's first Irish-Catholic mayor.

At 8 a.m. on Sept. 9, voting at Fay Hall at Washington and Dover streets ended and the union announced the results: At the 5:45 p.m. shift change, members would walk off the job.

And they did, setting off a labor war the echoes of which still reverberate today.

The police did not strike in a vacuum.

For one thing, they had been growing angrier over the years over their lack of any pay increase and a crushing workload - not only were they working 80 hours a week, they only got one day off every two weeks - and had to ask permission to leave the city even on their day off. They had to pay for their own uniforms and work and sleep in antiquated, vermin-infested police stations, some dating to before the Civil War.

And they were being surpassed in pay by other workers, such as trolley drivers, sheet-metal workers and city laborers. All around them, other groups of workers were striking, too, and often winning. In April, Boston telephone operators went on strike - and won a pay raise. The men who ran elevators struck and won. The people staffing Boston's theaters struck as well.

The day before the police went on strike, the Boston carmen's union was scheduled to vote on a strike date for the men who ran the city's trolleys and subways. Some 300 workers at Walton and Alpha lunch rooms across the city were on strike - ironically, a few days before they walked out, police sought to charge three of those picketers with violating a city ban on holding placards (a Central Division judge refused to issue the summons, saying the men didn't realize they were breaking a law and that, in any case, they weren't bothering anybody).

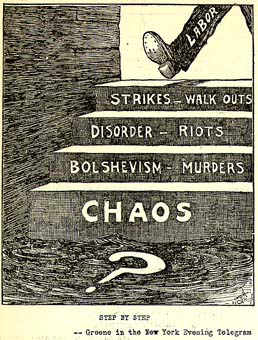

But it wasn't just workers who were restive: Capital, and the men in its employ, were responding as they always had: By decrying the strikers as un-American. The Russian Revolution gave them a new insult: Bolsheviks.

By September, the nation was in the midst of its first "Red Scare" - Communists and anarchists were hiding everywhere - the owners of the molasses tank that had burst in the North End a few months earlier at first tried to pin the blame on Italian anarchists in the North End. Boston Police themselves were not immune - in 1919, the force stocked up on high-powered weaponry to fight "the Reds." But once the officers walked out, newspapers and the sort of men who wore vests denounced the Boston officers as Communists trying to turn America Soviet.

Long before the strike, patrolmen had formed the Boston Social Club, not quite a union, to press for improved working conditions, but didn't really get anywhere - especially after the old police commissioner, who had introduced some reforms, died and was replaced by the state's new governor - named Calvin Coolidge - with a fellow Republican and non-Irish-Catholic mayor of Boston who had no sympathy at all for their requests for more pay and better hours. One of new Commisioner Edwin Upton Curtis's first acts was to order the social club to not even engage in lobbying at the State House without his permission.

Mayor Andrew Peters, who despite not having direct control over the police, did have to pay for the police budget - proposed a $200 annual increase. Officers said that was far too little to help them deal with inflation, let alone keep even with other groups of workers.

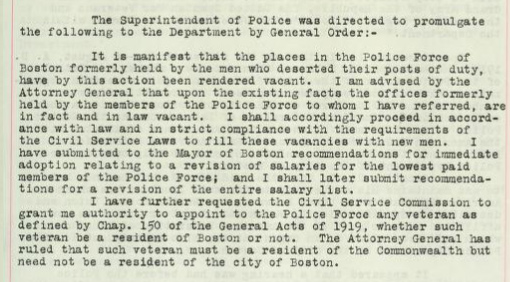

In the spring of 1919, the AFL announced it would begin accepting police locals. Curtis ordered his men to not even think of it. On Aug. 1, Curtis formally ordered the club not to become a union local. Members voted to create the Boston Patrolmen's Union and join the AFL. Curtis charged 19 officers with violating his direct orders against forming a union.

Mayor Peters, meanwhile, created your basic blue-ribbon commission, headed by local banker James Joseph Storrow (yes, as in Storrow Drive) to try to work out a compromise.

On Sept. 5, the Storrow commission recommended the patrolmen not unionize but that the police deserved better pay and working conditions and recommended creation of a committee to come up with details. Curtis and Cooldige rejected the idea, and now warned against a possible strike, telling the police that public order was more important.

On Sept. 8, Curtis announced he was suspending the 19 officers he said had violated his ban on unionization. That morning, union members began to talk about a strike. Peters and Storrow met with Coolidge, who refused to budge. The stage was set for that evening's vote.

The Boston papers were following every step of the process and news had spread around the country - the president of the American Bar Association even took note and condemned the very idea of a police union. So the sort of people who might enjoy not having police around took full advantage of it, as the local papers reported, as shown in the Sept. 10 Globe front page (which failed to note that most of the city remained calm).

Curtis took steps to try to replace the police on a temporary basis. He issued a request to the state civil-service commission for the names of 400 men he could hire as replacements. He began swearing in men at local businesses to act as "special" police officers.

As many as 250 Harvard men - students and professors alike - volunteered to break the strike after Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell urged them to cross the river and do their civic responsibility, the Harvard Crimson reports. One of the first to volunteer was Edwin Hall, a physics professor who was 63 at the time.

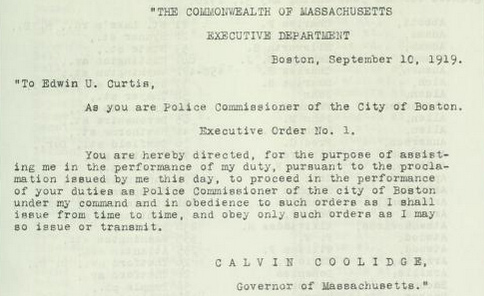

On Sept. 10, Mayor Peters, citing an ancient state law, dismissed Curtis and called in the Massachusetts State Guard to help patrol the city. This eventually broke the strike - and propelled Coolidge to the vice presidency after people outside Boston began crediting him for the move. For his part, the next day, Coolidge ordered Curtis reinstalled as commissioner and ordered in more guardsmen.

But in the meantime, working out of their temporary quarters in the main Quincy Market building, the guardsman fanned out across the city with rifles with fixed bayonets - even patroling the Chestnut Hill Reservoir in case somebody tried to blow up the pumping stations there.

Their complete lack of understanding of police work quickly showed: In a number of cases, rather than try to arrest ne'er-do-wells, they simply shot into crowds, killing people - from a 16-year-old in South Boston to a 21-year-old World War I veteran on the Common - in an incident in which a guardsman ran somebody through with his bayonet, but that person survived.

Support for the strike faltered. The AFL, it turned out, didn't much like the idea of police unions. AFL head Samuel Gompers urged them to return to work and telegramed Gov. Coolidge that the national union would not call for a Boston general strike to support the officers. A couple weeks after the strike started, he praised the Boston cops as "sacrificial victims" but said the AFL did not support the right of police to strike.

The union offered to call off the strike, but not unconditionally. Curtis fired the 19 organizers, then, eventually, on Sept. 13, all the strikers - and ordered them barred permanently from ever again working as Boston police officers. Curtis noted the action in a memo in the official police log for Sept. 13:

Like Reagan with air-traffic controllers, he eventually hired an all new force - more than 1,500 men. And, ironically, he agreed to pay them $1,400 a year - more than the striking officers were making - to pay for their uniforms and to give them pensions.

The new officers did not unionize. It was not until 1965 that Boston police officers again formed a union.

In the November elections, Calvin Coolidge, up for re-election, won overwhelmingly, in part because of his perceived handling of the strike.

The next year, Warren Harding picked him to run for vice president. When Harding died in 1923, Cooldge became president.

David Shribman looks at the continuing questions the strike raised.

The strike raised serious questions about whether workers in one segment of society lacked the labor rights, including the right to strike, of workers in the rest of society - and whether the public's right to safety and security trumps workers’ rights to strike.

"The strike was crushed but the issue was not settled," Richard L. Lyons wrote in the New England Quarterly. "It remains unsettled to this day."

Roll Call has way more info on the strike, what led up to it and what followed it, including a detailed timeline and photos and bios of many of the striking officers.

Ad:

Comments

'the given day' dennis lehane

good dennis lehane book about this time in boston history.

Loved that book. I like the

Loved that book. I like the Babe Ruth weaving in the story.

Just some context.

There were anarchist bombings in 1919.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/1919_United_States_anarchist_bombings

Two in June occured in Massachusetts.

And then later was the Wall Street bombing in 1920.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wall_Street_bombing

Such were the times.

And a May Day riot in Roxbury

So, no, not peaceful times.

Massachusetts' first gun

Massachusetts' first gun control laws passed in 1909 were a response to fear of Italian anarchists and Scotts/Irish labor groups arming up for acts of political violence. Later on this discrimination would expand to African Americans during the migrations north for factory jobs during WW1 and WW2. The Yankee Brahmins and later Curley's lace curtain Irish ethnic identity blocks were terrified that the working class minorities might riot against their entrenched political machines. This is an era when BPD had Maxim machine guns at the ready prepared to go all trench warfare on strikers. And this wasn't even into the prohibition era of gangsters running around knocking over banks and bootlegging yet!

Sometimes the 'good old days' were anything but.

Police strike planning took place above J.J. Foley's

Much of the police union activity occurred on Dover Street, later rebranded as East Berkeley Street, in the space above J.J. Foley's. There's a nice plaque there. God Bless the striking officers who fought for a living wage for those of us who came later. Ocean Frank, we've got this from here.

Shut up

you commie! Listen to this guy talking about unions over here! Go back to Russia with all that!