The English capital crime that's still on the books here, even though it's a remnant of our slave days and nobody's been tried for it since 1782

Recent weeks have seen the phrase "high crimes and misdemeanors" re-enter the public discourse. Turns out there are also "low crimes," one of which used to carry a particularly gruesome penalty in New England - and which is still listed as a capital offense in Massachusetts lawbooks even though it was used primarily as a way to punish slaves, such as a slave known only as Mark, whose tarred remains were kept on public display by the side of the road in Charlestown for more than 20 years.

If you look up the official Massachusetts definition of "murder," at MGL Chap. 265 §1, you'll find four specific reasons for which a person can be charged with that offense. Three are what you'd expect: Causing somebody's death with "deliberately premeditated malice aforethought, or with extreme atrocity or cruelty, or in the commission or attempted commission of a crime punishable with death or imprisonment for life."

But the fourth reason? Petit treason - although the law doesn't define what that is. For that, we have to go to the history books.

English settlers brought the concept of petit treason over with them from the old country. In England, the legal system had two types of treason - "High" treason, or an offense against the sovereign grave enough to warrant death, and "petit" or "low" treason - which also warranted death, but which involved crimes of a lesser against his or her superior, if not quite the king.

In England, that ranged from killing a superior (who could be a church prelate, a master or, if you were a woman, a husband) and eventually extended to lesser crimes - theoretically, in England, somebody could be put to death for using an employer's official seal on a document.

In the colonies, at least in New England, the crime was limited to murder, although we kept the idea that a woman killing her husband had engaged in "petit treason."

What also distinguished petit treason from regular old murder was the punishment: Rather than just being led to a gallows to be hanged, men convicted of petit treason were dragged to the gallows and hanged and then could be "gibbetted" - their bodies put on public display (in England, the bodies could also be disemboweled and castrated, the heads were cut off and then they were carved into four pieces, i.e., quartered). The ladies got what was considered a more humane punishment - they were burned to death, although usually with a noose around their necks, which was pulled as the flames were set, so they would die quickly from hanging rather than suffering much from the fire.

Only two people were ever sentenced to death for petit treason in Massachusetts - two slaves, named Mark and Phillis, in 1755 in Charlestown.

According to an 1883 account by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the two were among several slaves belonging to John Codman, a sea captain and trader who lived in Charlestown, in an era in which slavery was legal in the colony (in fact, Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery, in 1641, and only outlawed it in 1783).

Three of the most trusted of these, Mark, Phillis, and Phebe,—particularly Mark,—found the rigid discipline of their master unendurable, and, after setting fire to his workshop some six years before, hoping by the destruction of this building to so embarrass him that he would be obliged to sell them, they, in the year 1755, conspired to gain their end by poisoning him to death. ...

Mark ... professed to have read the Bible through, in order to find if, in any way, his master could be killed without inducing guilt, and had come to the conclusion that according to Scripture no sin would be committed if the act could be accomplished without bloodshed. It seems, moreover, to have been commonly believed by the negroes that a Mr. Salmon had been poisoned to death by one of his slaves, without discovery of the crime. So, application was made by Mark, first to Kerr, the servant of Dr. John Gibbons, and then to Robin, the servant of Dr. Wm. Clarke, at the North End of Boston, for poison from their masters' apothecary stores, which was to be administered by the two women.

They eventually obtained a supply of arsenic - which Mark procured after going over to Boston in a ferry to pick it up from Robin. They mixed about seven doses into drinks and some food served to Codman - specifically, they put it into his "barly Drink and into his Infusion [tea], and into his Chocalate, and into his Watergruel [watered down porridge]" - and he eventually keeled over and died.

They were unable to keep the plot secret and on July 2, 1755 - just one day after Codman's death - Mark was arrested. Phillis was arrested not long after - as was Robin.

A month later, a grand jury sitting in Cambridge formally charged the three with petit treason. In the indictment, Massachusetts Attorney General Edmund Trowbridge accused Phillis of "not having the Fear of God before her Eyes but of her Malice forethought contriving to deprive the said John Codman her said Master of his Life and him feloniously and Traiterously to kill and murder." Mark and Robin, the indictment continued, did "feloniously & traiterously advise & incite procure & abet the said Phillis to do and commit the said Treason & Murder aforesaid against the Peace of the said Lord the King his Crown and Dignity."

Mark and Phillis were convicted, and sentence of death was pronounced upon them in strict conformity to the common law of England. On the 6th of September, a warrant for their execution was issued, under the seal of the court, commanding Richard Foster, Sheriff of Middlesex, to perform the last office of the law, on the 18th of the same month; and upon this warrant the sheriff made return upon the day of the execution.

Phillis was buried somewhere. Mark's body, though, was coated in tar and then gibbetted - his body hung from chains on an iron stand at Charlestown Common - in what is now Somerville (the punishment was also used for people charged with piracy; their bodies would be hung on Nix's Mate, an island at the entrance to Boston Harbor).

Mark's remains were still there, 20 years later, when Paul Revere made his famous ride towards Lexington in 1775; in a letter, Revere wrote:

After I had passed Charlestown Neck, & got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on Horse back, under a Tree. When I got near them, I discovered they were British officer. One tryed to git a head of Me, & the other to take me. I turned my Horse very quick, & Galloped towards Charlestown neck, and then pushed for the Medford Road.

In 1782, Priscilla Woodworth of Blandford was charged with petit treason for allegedly killing her husband, Nathaniel, by poisoning him with arsenic. She was, however, found not guilty.

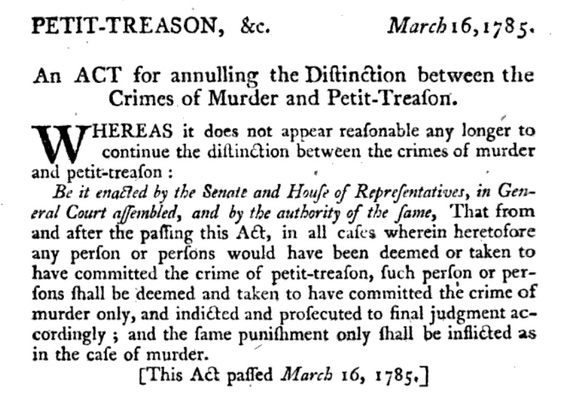

Three years later, the state legislature repealed the distinction between petit treason and murder - meaning no more difference in how sentences were carried out. But what is now basically a historical footnote remains enshrined in state law.

Ad:

Comments

Where is the body now? Can

Where is the body now? Can we get ot back?

1775

Paul Revere rode in 1775, not 1755

The copy editor needs to be cashiered

Yep, 20 years after the executions. Mistake fixed.

"Humane" burning

Thanks for including the detail that women were strangled before the flames became unbearable. That slightly mitigates the horror I experienced when I read about Phillis's execution (having found this account out of curiosity about petit treason mentioned in your previous post). This is the first time that I've read about execution by burning in the colonies.

A second woman was burned at the stake

In 1681, a woman named Mariah who was enslaved in Roxbury was convicted of arson. While petit treason isn't mentioned in the court records, it probably explains why she was burned to death. When she was killed, an enslaved man named Jack was hanged for an unrelated arson. His body was cut down and burned in the fire with Mariah. It's a truly horrifying case.

More on Mariah and Jack, as well as Phillis and Mark, in episode 27 (starts at 11:30) of the HUB History podcast.

Hub History

The Hub History episode is amazing. The story is heartbreaking. I wish that history was different.

I think she was convicted of arson, though, not petit treason

Not that that matters in terms of the punishment, of course, but this account by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts (which I found after running across a reference to Maria and did a search for more info on her) makes it sound like she pleaded guilty to arson for burning down the house belonging to her master, Joshua Lambe of Roxbury, not for killing anybody.

She was charged around the same time as Jack, who pleaded not guilty to burning down a house in Northampton, but who was then found guilty by a jury.

History Camp March 14

Have you signed up to give a presentation? This would be great with some gruesome slides.

Total Confusion between the punishment & crime

You wrote:

Turns out there are also "low crimes," one of which used to carry a particularly gruesome penalty in New England - and which is still listed as a capital offense in Massachusetts lawbooks even though it was used primarily as a way to punish slaves,

You are mixing the particularly gruesome method of punishment with the crime.

The crime was "petit treason" -- which was the killing of a master by a person under the master's authority. You associated it with Slavery because that is a popular topic these days although it could apply equally well to the murder of a Master by an "Indentured Servant" or even an Apprentice. That's the crime and as you pointed out that on March 16, 1785 the Great & General Court [aka the Legislature] essentially repealed the specific crime by including such actions under the more general crime of murder. So as of that day the specific charge of petit treason has no longer existed.

The punishment meted out to men*1 convicted of petit treason was to be dragged to the gallows and hanged and then "gibbetted" - their bodies put on public display. This punishment was also applied to men accused and convicted of Piracy.

In the case of Piracy the place where your body would be displayed was upon Nix Mate in the middle of Boston Harbor. This process would of course be consistent with the Puritan view that punishment was not just for the guilty -- but also a deterrent to others. Thus for far less serious crimes the guilty party might be publicly exhibited for ridicule in the Stocks or Pillory for some part of a day [typically a few hours].

The Pirate William Fly and two others were convicted hung and gibbetted on Nix Mate in 1726.

So to sum it up --- since petit treason became just murder -- the only way that gibbetting could still be on the books would be if Piracy was still punished in the manner of the 18th C.

*1

You wrote

Thanks for the extra info, but ...

No, the different punishment WAS part of the point of petit treason. Petit treason was, at least in the colonies (as opposed to England) the same as murder, but common murderers didn't have to worry about being dragged in public to the gallows or burned at the stake (ditto for people convicted of other capital offenses, such as Mary Dyer, who was walked to the gallows for the crime of being a Quaker). Nor were the bodies of people convicted of murder then put on public display as a warning.

Not sure why you're so insistent that this was not a slave issue, but it was. In the New England colonies (I don't know what goes on past the Berkshires or south of Long Island Sound), it was used almost entirely to discipline slaves.

ARGH!!! -- You forgot Piracy

The point I was making was that Gibbetting the extreme punishment was reserved for a special extreme crime -- not just "ordinary murder."

The perp would not be gibbetted if say Paul Revere poured hot silver into John Hancock's mouth converting him instantly into a life-sculpture. That would have been murder most foul and Paul would have hung. However, his body would have been released for a Christian Burial. Paul and John being essentially equals and the act of murder being foul but not beyond the bounds.

But I as Pirate seizing Mr. Hancock's ship even as it might be smuggling some untaxed Madeira Wine and in the process killing Mr. Hancock's ship's master --Well I would hang until dead and then my body would be left to rot or be eaten by Seagulls while hanging from a pole on Nix Mate to warn others approaching Boston of the impertinence of the Act of Piracy.

This was done several times in Boston when Pirates were seized by the authorities [such as 1726] -- Piracy being perceived as a threat to the normal order. In a couple of cases, the Pirate was bound-up and shipped to London for trial, and eventual punishment, or tried in Boston, and then shipped to London for the sentence.

Similarly, if Paul had an apprentice who did the "silver soda" trick on Paul -- that would have been in the same category as Piracy. It didn't matter whether the doer of the the Thermal Deed was a Slave, an Indentured Servant or an Apprentice -- killing your master was not permitted in a Civil Society [Boston or London] and your rotting corpse would be displayed as a warning. Think Kirk Douglas in Spartacus and the long line of Crucifixions on the Appian Way after the revolt of the Slaves was put down by the Roman Legions.

Note that in some jurisdictions such as Texas there still is an aggravation factor which can be applied -- if for instance in the commission of an armed robbery -- while escaping you kill a Police Officer. The act of murder of a Police Officer thereby upping the crime to Capital Murder and making you eligible for the Death Penalty.

I don't think we're really disagreeing

Yes, gibbetting was reserved for a special sort of crime. Piracy was an example. A slave killing a master was another.

But a slave killing a master was still a type of murder. Why would it be considered different from, say, a man killing his business partner? That gets us to a consideration of the position of slaves in colonial Massachusetts.

You yourself noted that the Puritans put emphasis on certain punishments as warnings. Look at public stocks - or how children were supposed to be brought to hangings. Who, exactly, would the province be trying to warn by gibbetting Mark the slave? And why wouldn't they feel the need to do so in other cases of people convicted of killing somebody?