Stony Brook: Boston's Stygian river

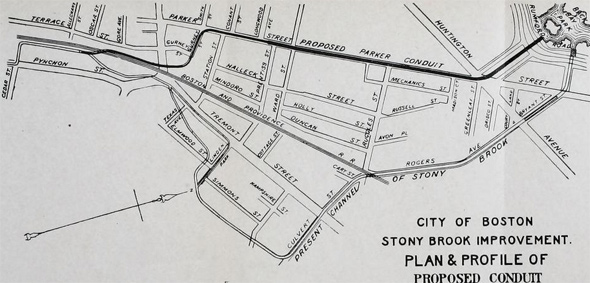

Turning Stony Brook into an underground river in 1888. Source.

Boston was in the middle of one of those winter thaws we always seem to get: From a low of -7 on Feb. 5, the temperature shot up to 55 on Feb. 9, National Weather Service records show. On Feb. 10, with the temperature still a relatively balmy 40, rain started around 7:45 a.m. And then it kept coming. For three straight days, it rained. By the time the rain stopped, around 2:45 p.m. on Feb. 13, 1886, nearly six inches had fallen, enough to melt another two inches of accumulated snow and ice.

But while the air was above freezing, the ground wasn't, and all that water and melting snow ran into Boston's rivers and brooks. In Roxbury, Stony Brook burst from its banks where it entered an underground culvert near where Madison Park High School and the Whittier Street Health Center are today. That created a gurgling flood that inundated 63 acres of densely packed blocks, home to thousands of people and numerous factories - including the world's largest rubber manufacturing plant.

Stony Brook had flooded before - in fact, it had become known for its "freshets" every spring - and the city of Boston, and before it, the city of Roxbury and the town of West Roxbury had taken some steps to at least reduce the flooding. This included putting a small part of the brook in a culvert just north of today's Roxbury Crossing and deepening, widening and straightening out the brook south of Forest Hills.

But in 1886, faced with thousands of people trapped in their homes, and lawsuits from the owners of factories forced to shut down, Boston started what turned into a decades-long project to create Boston's underground river - a 7 1/2-mile waterway on which the sun never shines. Throw in all the marshes that were filled and the tributaries that were also covered and you end up with a project to rival the creation of the Back Bay, one that affected hundreds of acres of land from Hyde Park to the Charles River.

When Europeans first started settling the land along and south of Boston Harbor, Stony Brook was a slow-moving stream clean enough that people could go trout fishing along its banks. Like the Charles River into which it flowed, the brook was a tidal estuary, at least upstream to about what is now Roxbury Crossing.

Stony Brook in the area of the intersection of Tremont and Ruggles streets in 1843 (source):

Stony Brook did tend to overflow its banks in the spring, but that didn't much matter when it and its tributaries - Canterbury Brook through what is now Dorchester, Mattapan and Roslindale, Bussey Brook, through what is now West Roxbury and Roslindale and Goldsmith Brook, through what is now Jamaica Plain - were mostly surrounded by marshes and low-lying woodlands (some 700 acres of them just along Stony Brook).

1852 map showing Stony Brook and its tributaries (source) - but not the connection from Muddy Pond (which was later renamed Turtle Pond). Roxbury and Dorchester were still independent municipalities; Hyde Park was part of Dorchester and West Roxbury, Roslindale and JP part of Roxbury.

As Boston grew, though, people moved closer and closer to the brooks. Factories, including breweries, moved right up to the very banks of Stony Brook, attracted to the brook as a source of water (think beer) and power - and as a sewer to dump stuff into. When one of the first railroads out of Boston was built, south to Providence, it followed Stony Brook through the low valley it had eked out of the surrounding countryside.

By 1851, the area along Stony Brook was so built up that spring floods had become really annoying. As Henry H. Carter noted in an 1892 article chronicling the brook's issues in the Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies, the town of Roxbury took what had become a classic Boston-area approach to water and sewer problems: Bury them.

The town paid to have part of the brook, between Ruggles Street and what is now Columbus Avenue turned into a culvert that was then covered and sold off as buildable lots (back then, Columbus Avenue was called Pynchon Street, in honor of the guy who founded Roxbury, William Pynchon, who, in equally Boston-area fashion, was driven out as a heretic, so he moved west and founded Springfield). South of there, and upriver, the town of West Roxbury, meanwhile, tried to solve the flooding problem by widening, straightening and dredging the brook.

At a gatehouse at the mouth of the culvert, burly men worked to clear flotsam from the brook (from Carter's report):

A city built right up to the banks of the brook (photos by Edgar Sutton Dorr; the second showing the view north from JP, towards the Fort Hill water tower):

The flooding continued, at least in the areas south of Roxbury Crossing. In West Roxbury, officials identified some 100 homes that would get flooded pretty much every spring.

The culvert was extended north a bit. The flooding continued south of it.

And then came those four days of non-stop rain in February, 1886. The culvert proved unable to handle all that water, in part because it wasn't built all that well and parts collapsed, reducing the flow it could handle, Carter wrote. With nowhere else to go, the water rapidly flooded the area, from roughly Roxbury Crossing between Tremont Street and Shawmut Avenue to just north of today's Melnea Cass Boulevard - in places up to twelve feet deep.

The breweries and factories - including the Boston Belting Co., at the time the world's largest rubber manufacturing plant - had to shut down. The city's Overseers of the Poor organized a flotilla of relief rowboats to deliver loaves of bread - baked at the city jail - and coal and cooking oil to trapped residents, from a launch point at what is now the intersection of Whittier (then Culvert) and Cabot streets.

On Feb. 13, the Boston Globe described the flooding, which spread from the entrance of the culvert near the intersection of the long gone Clay and Simmons streets - today land between the Whittier Street Health Center and Madison Park High School:

Passing under Clay Street is the great sewer, and when it is discharged into Stony Creek, a mass of yellow, turbulent water seeths [sic] and fiercely boils up like a geyser. From here the flood pours through the channel of the creek, ten feet above its normal level, burying Simmons street under eight feet of water. Here, the waters spread, and although Salsbury, Mahan avenues and Donning street, where the water is from ten to twelve feet deep, down to Windsor street, the angry waters reign supreme between Tremont street and Shawmut avenue.

Clay and Simmons are near the bottom of the map - near the top, note that Stony Brook still flowed above ground, near its confluence with the Muddy River (source: Atlas of the Late City of Roxbury, 1873):

The Boston Journal reported on the relief effort:

At one house, their loud "Hullo!" brought a woman to the window. "We've got food enough," she said, "only we can't cook it. Our coal is all down cellar." No further explanation was necessary, and a stalwart boatman lifted a basket of coal and wood through the open window. The smoke that poured from the chimney a few minutes later showed that they were making good use of the fuel.

Nobody died from the flooding itself, although there were some people who died in their homes of other causes (in one case of "consumption," what we now call tuberculosis); their bodies, in caskets, had to be floated in boats down the street to hearses waiting on drier land. Some of the gawkers who came to see the flooding only narrowly escaped death. As the Globe reported:

In one instance this nearly cost the life of a horse. A wagon load of men attempted to cross Culvert Street beyond No. 11 engine house and, being caught by the swift current, was swept into a hole made by the waters and swamped. All that could be seen was the horse's head and a number of men floating about. The accident caused great excitement, and a number of police officers hastily put off to their assistance in a boat. The animal had no idea of sacrificing itself to its driver's stupidity, and after a heroic effort swam out with the wagon and its half-drowned occupants, amid the cheers of the spectators.

Within a few days, the flood had receded, but its repercussions had not. Faced with the widespread damage, not to mention a lawsuit from the Boston Belting Co., whose plant was located right in front of the Stony Brook gatehouse - and whose owners had warned of just such a flood years earlier - Mayor Hugh O'Brien wasted no time appointing a commission of three civil engineers to come up with a solution, to end the flooding threat once and for all.

In their report, filed on July 27, 1886, the engineers wrote they had first considered building a series of retention ponds in West Roxbury to hold overflows from the brook, but rejected that idea because they estimated the city would have to buy up some 1,000 acres of land, and build a complicated series of dams, culverts and control mechanisms to get the water from a future raging Stony Brook to the new ponds.

Instead, they decided to go big with the tunnel idea: They urged the city to divert the entire brook, from at least Forest Hills, into a series of large tunnels - some between 13 and 17 feet tall and 15 feet wide - which would be large enough for a Biblical flood of roughly 12 inches of rain in just 24 hours. This wouldn't stop the flooding further upstream, in West Roxbury, but they added that that would be easy enough to fix - just build an all new tunnel to divert Stony Brook to the Neponset River at Dorchester Lower Mills (this tunnel was never built).

The city quickly appropriated $600,000 for tunneling between Roxbury Crossing and the Fens, which began in October, 1887, and took about a year to complete. When done, Stony Brook now flowed entirely underground downstream of Roxbury Crossing to a new gatehouse - designed by architect H.H. Richardson - at the end of what is now Forsyth Way on the Muddy River in the new Back Bay Fens that Frederick Law Olmsted was overseeing.

In several places, the work involved creating an entirely new path for the brook to follow, such as along Mission Hill, as shown in Carter's report, which also showed some of the dimensions of the new underground Stony Brook:

The city actually left the old channel in place and continued to let some water flow through it so that the Boston Belting Co. could continue to draw water.

One of the engineers on the project was Edgar Sutton Dorr, a graduate of English High School and MIT who worked for the Boston Sewer Department. In addition to his professional talents, Dorr was a photographer, and many of his photos (of both Stony Brook and other sewer projects, as well as family members) are now online in a collection maintained by the BPL.

Dorr took this photo from inside a large Stony Brook tunnel, at a "bellmouth" where it split into two smaller channels; engineers had to do that in some places due to underground conditions:

Dorr oversaw work to create tunnels out of some of the tributaries, in this case Canterbury Brook after it left Scarborough Pond in Franklin Park:

But, of course, the problems didn't end - on either side of Roxbury Crossing.

At the northern end, the problem was no longer large amounts of water, but large amounts of stench, coming from the increasing amount of sewage from the fast growing neighborhoods of Jamaica Plain, Roslindale and West Roxbury, whose sewers mostly poured into the brook. And with the once pristine brook reduced to a large sewer, Olmsted's Fens became a giant cesspool.

Ironically, Olmsted had originally designed the Back Bay Fens to fix the odor problem, caused when the sewage deposits on the tidal flats of the Muddy River, near where Stony Brook joined it, were exposed to the air at low tide. Olmsted had a dam built across the Muddy's confluence with the Charles so that the Fens would always have enough water to cover those flats (and had lots of salt grass planted along its bank).

But in 1905, the state began building a dam across the mouth of the Charles, because the same issue was happening along the entire Back Bay riverbank. That turned the Charles River Basin into a freshwater lake - and tides no longer flowed in or out of the Fens even as the sewage from Stony Brook kept piling up and up - especially with the collective wastes of 90,000 people in JP, Roslindale and West Roxbury flowing down it.

The city hired more contractors for the next fix: Build a second gatehouse next to the first one, then connect that to a third gatehouse a few blocks downstream, right at the banks of the Charles, where it would connect to a new sewer main along the river and across downtown to Nut Island, where everything would just be washed out to sea (or so they thought).

Meanwhile, south of Roxbury Crossing, flooding continued along Stony Brook, now essentially a large ditch that ran along the train tracks to Forest Hills - upstream of which it still flowed in a slightly curvier fashion. Over the years, the city slowly converted that stretch of the brook into an underground tunnel as well - sometimes moving it 30 to 50 feet to accomodate an expanding rail line.

In 1898, when the Metropolitan Water Works installed a new water main at Morton Street, just east of Forest Hills station, it went across Stony Brook roughly through where the old Laz parking lot was until recently, after crossing under Hyde Park Avenue just north of Tower (source):

By 1905, the brook had been put underground north of Green Street in JP - on the map, look south of the train tracks (Source):

Sue Pfeiffer of Roslindale has a binder that includes a couple of photos from 1900 and 1901, when the brook was being put underground near where the state lab now stands on South Street near Asticou Road:

Just a little bit south of there (near where, today, the MBTA sometimes stores Orange Line cars), Stony Brook was joined by Bussey Brook, which starts in Allandale Woods on the West Roxbury/Roslindale line and flows through what is now the Arnold Arboretum. The city built what is basically a large funnel for Bussey Brook to flow into Stony Brook.

And the city continued to slowly entomb the brook in more and more tunnels south of Forest Hills. By 1924, according to a West Roxbury atlas, the brook flowed in tunnels north of Tollgate Road. In the 1920s and 1930s, the city worked to cover most of Canterbury Brook along what is now American Legion Highway (original proposed name: Canterbury Parkway) in Mattapan and Roslindale, because of repeated flooding on the grounds of what became Boston State Hospital.

Eventually, city tunnelers reached Enneking Parkway in Hyde Park, where, today, the underground river begins, at a dual pair of culverts just up from Gordon Avenue.

But out of sight stopped being out of mind in the 1980s, when a lawsuit by the city of Quincy against the state resulted in a court order to clean up Boston Harbor. Although construction of the Deer Island treatment plant got the most attention, the new MWRA also began work to stop raw sewage flowing into the harbor from sewers that connected to storm drains - including ones pouring into the Charles River. It turned out Stony Brook was one of the largest contributors of sewage and toxic chemicals into the Charles, because it was still collecting sewage from well upriver and dropping it into the Charles (and even the Fens) during and after heavy rains.

The Boston Water and Sewer Commission spent several years - and more than $40 million - to build new sewer lines to handle waste and keep it out of Stony Brook. And it went after more than 200 businesses and homes that had illegal connections to the brook, forcing them to shut off their flows of wastewater. By 2006, the BWSC had reduced the annual amount of sewage flowing into either the Charles or the Muddy River from about 44.5 million gallons a year to just 130,000 gallons.

The brook's path today

Today, the underground river zigs and zags through Hyde Park up to the Northeast Corridor train tracks, which it follows until a point near American Legion Highway and Hyde Park Avenue, where it crosses and goes under Hyde Park Avenue and along American Legion, and continues right under the intersection of Cummins Highway and Canterbury Street, until just past Mt. Hope Street, where it veers north and goes by Brook Street and picks up Canterbury Brook.

It crosses Hyde Park Avenue, the train tracks and Washington Street to the west at Pagel Playground - where it picks up the underground Roslindale Branch (which flows roughly under the right of way for the Needham Line) - then crosses back over to the east of Washington and Hyde Park Avenue just north of Ukraine Way in Forest Hills. There, it jags a bit more east past Tower Street, heads north under the Arborway and the MBTA bus depot before following a jag back to Washington Street (it flows next to the basement of Doyle's) at Green Street. From there, it follows the Southwest Corridor to Malcolm X Boulevard, crosses under the tracks to Parker Street and heads north to the Fens.

You can follow the entire route, and the routes of its tributaries, in a map in this BWSC report. Search for "Boston Water and Sewer Commission - IDDE Priority Ranking" (unfortunately, the map does not show street names).

Finding signs of the brook

Although Stony Brook is underground today, it's still possible for the intrepid explorer to find traces of it - even if you're not one of those people who enjoys dropping into giant sewers and exploring (some amazing photos there, but kids, don't try that at home). You can start at the brook's beginning in Stony Brook Reservation, where Roslindale, West Roxbury and Hyde Park come together. From Washington Street, head south onto the parkway. At the four-way stop, turn left, then look for a parking lot and pull in (if it's full, there's a larger lot across the road). And voila, Stony Brook is right there - although it's not very big, and is sometimes dry in late summer:

If you walk onto the path that starts at the lot, take the left fork and you can see more of the swamp and the marshes it comes from on the left. Follow the paved path and enjoy walking through the forest primeval until you see a large unpaved path going off to the left. Follow that and you'll get to Turtle Pond, the source of the brook.

If you want to see where it begins its underground voyage, get back in your car and head down Enneking to Gordon Avenue. Park there and, very carefully, walk on the right side back into the forest (there's no sidewalk). Past the last house, look down, to your right (caveat: it's really boring):

The former end of the brook is probably more worth a look than the Hyde Park culvert. Along the Fenway, across from Forsyth Way, you'll find the two gatehouses. The one in the foreground is still in use, and drains into the Muddy River, although not so much these days. The second gatehouse was shut in 1970 and later renovated for use as a visitor center for the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

At the Muddy River itself, you can see the tunnels from which Stony Brook used to pour:

If you continue up the Muddy River to Charlesgate, you'll mostly be struck by how awful it looks with a large highway overpass stuck in the middle of it. Keep going. Cross Beacon Street and continue under the ramp down from the interchange to Storrow Drive. And behold the third Stony Brook gatehouse, the one that connected it with that city sewer that once ran along the banks of the Charles - and the one that you may well have seen scores of times while heading to the airport or New Hampshire and briefly wondered what it was.

As long as you're there, walk to the rear of the building and picture standing right on the bank of the dirty water - after the city built the gatehouse, the state dumped lots of fill along the Boston bank to create the land that became both Storrow Drive and the Esplanade.

Back to the south, you can walk along Bussey Brook through the Arnold Arboretum (enter through the gate at Walter and Bussey streets, where you'll find parking). You'll know when it crosses the main path when you hear a gurgling sound from one of the manholes. Follow it into the rhododendron area and after a few steps, you'll swear you're in a mountain glen somewhere, not in the middle of New England's largest city.

Follow the brook across South Street to the more wild Bussey Brook Meadow and go down the path. Eventually, on your right, you'll see an odd gate-like thing. This is where Bussey Brook drops eight or nine feet down into a culvert that crosses under the train tracks to meet Stony Brook at a juncture under the intersection of Hyde Park Avenue and Tower Street. Probably the best time to see it is on a snowless winter or early-spring day, before the vegetation springs up and makes it difficult to get to:

The grates are to keep tree branches and other stuff out of Stony Brook.

There are more subtle signs of the brook - or where it used to be - to find. About ten years ago, Mark Bulger compiled an interesting set of articles on his search for signs of the brook. One of the things he mentioned was looking at maps for street names that might indicate where the brook used to flow.

So go to Google Maps and search on Brook Street Roslindale MA. Notice the sort of gray "road" between Brook and American Legion Highway. It's an easement showing where the brook used to flow above ground, but is now underground (and Canterbury Brook used to flow into Stony Brook at the end of, ta da, Brook Street). Follow the easement north. It keeps going and crosses under Neponset Avenue. Now, should you happen to be in the area and find yourself on Neponset Avenue, just before it's joined by Halliday Street, park and look down and you'll see something odd: Five BOSTON SEWER manhole covers - right over the underground Stony Brook:

Call that Google Map back up and keep following the easement. It crosses under Hyde Park Avenue and seems to end at Pagel Playground, along the Northeast Corridor tracks. In fact, it flows under a walkway at the northern border of the park. If you go there, look for a manhole cover in the grass to your left - it would drop you down into the brook. Ignore the remains of a tunnel under the train tracks - that has nothing to do with the brook (it's a pedestrian tunnel the city mostly filled in a couple decades ago after nearby residents complained about drug users and prostitutes going down there; in fact, if you try to take pictures of the tunnel, expect a visit from one of the neighbors, who might just yell at you if they think you're from the city and looking to re-open the tunnel).

The brook comes out the other side of the train tracks and what do you see? A street called Brookway Road. Interesting name. Compare the curvy road's layout with the route the brook took in 1914, when it was still aboveground (source).

Finally, if you want to keep up with the levels of the brook, BWSC has a page where you can check the levels in the main Stony Brook conduit, via a meter under Parker Street just south of Ruggles Street, and in the old Stony Brook conduit, the one that originally led to the Muddy River, and which is still open, via a meter under Forsyth Street, just south of Greenleaf Street.

Ad:

Comments

Great stuff

Well done, Adam - terrific photos and history.

FYI: As the Casey Arborway project nears completion, landscapers and stone masons are currently creating a "dry riverbed" surface feature indicating the course of Stony Brook as it crosses the Arborway. It begins south of the Arborway and just east of Hyde Park Ave (near the Residences at Forest Hills apartment complex under construction in the former LAZ parking lot) and runs diagonally north across the median towards the bus yard. There will eventually be a historical marker telling some of its history.

Wow, that's cool

Ghost Arroyos does something similar with the hidden waterways of San Francisco, but on a less permanent basis.

And thanks for the kind words!

Hiding in Casey Arborway map

You can spot the Stony Brook landscape feature hiding under the trees in this rendering:

http://arborwaymatters.blogspot.com/2014/10/casey-arborway-halloween-tre...

Fabulicity !!!

Too bad the Globe doesn't write so many interesting and informative articles, intelligent people might read it again.

This is so awesome

I was just thinking about this the other day when I was driving up Enneking Parkway.

I've always thought it would be a cool project to mark where the underground rivers flow with blue lines on the sidewalks above.

Great job on this post and research.

Thanks!

I have to admit, I became a bit obsessed with this topic (ask my wife and daughter) - I don't think I've ever spent so much time researching something, I just kept finding more and more interesting stuff, which would lead me to yet more interesting stuff (including what might be my next research topic - the old Charles River seawalls).

It's also kind of amazing how much material related to this is available online. I thought I'd have to spend some serious time with microfilm at the BPL to read newspaper accounts, but it turns out the BPL gives library-card holders access to a number of online newspaper databases, and they have search tools and everything (the databases are actually available to any Massachusetts resident - if you don't have a BPL card, or don't know your card PIN, you can get an "e-card" that will let you in).

Great job Adam !!!

Too bad the City doesn't make certain other things so easy to find and accessible........

Like Mayor Curley's desk?

Heh, I din't do it.

Daylight stony brook

Environmental remediation, daylight the river.

Canterbury Brook

Turns out there's roughly 4,500 feet of it that still flows wild. And given that a big part of the old state-hospital grounds under which its conduit flows is now a nature center, might be interesting to look at daylighting there (of course, the issue would be cost).

Bussey Brook through the rhodedendrons at the Arboretum is also really cool - you really feel more like you're in a mountain glen than in Roslindale (nothing against Roslindale ...).

You can actually still see it

You can actually still see it in a parking lot in the JP section between green st and stony brook along with don't dump drains into charles signs, where it flows almost entirely under parking lots, the area was rezoned to allow more development in the recent plan neighborhood plan from the BPDA, should have included day lighting it, would make for a really nice park that could tie into the existing SW corridor.

'Daylight the river'

OK, so how's this for a curveball...it's been covered for a century. What are the odds that fish and other aquatic thingies have adapted to low (or no) light conditions? We may have our own species of blind crayfish here. Sonar kibbies. Painted turtles that are unpainted because, well, no light.

All because of AG's well researched post.

I propose we give the sonar kibbie the Latin name (um, I ain't Sumo prime) Pisces Adamus Gaffinus.

They aren't trapped under there

The water flows, and they can swim.

really?

i dont know enough to say but how many fish really would be able to traverse this? miles of pipe.

Old Haffenreffer barrels too!

Old Haffenreffer barrels too!

Legends based in truth

I may have commented before that family history (oral) stated that my great-grandfather was a laborer for a time on the Stoney Brook projects and he noted that in places it was big enough to run a horse and cart through it. The images bear this out.

Also as you can see the state-of-the-art in those days was stone, brick, and mortar and while that may have allowed for a majority of channeling of the water, over time the earth will shift and settle so it can cause leaks to happen. If you trace some of the tunnels now with modern satellite maps you can still locate some interesting sets of trees that follow nearly straight lines. The roots fo these trees are following the water leaking underground from the tunnels.

I'd also caution that we not accept any specifics on location based on these old maps since survey marks may have moved and streets shifted over time. Also along with the major project there were also additional smaller feeders that drained into the larger tunnel system. Based on what I have learned from past generations and family stories the variance could be several hundred feet or more.

Yep, things move

In 1981, the MBTA had about 600 feet of the conduit south of Tremont Street (not sure exactly where) moved roughly 50 feet to make way for the new Orange Line.

I Saw It

My dad took me over there, right around Ruggles Street on a Sunday AM and we snuck onto the construction site and looked into the opening. It was right next to where police headquarters is now.

At least they wrote it down.

I heard a story in the eighties from a BWSC guy about pipe work on Poplar St near the golf course.

They were looking for the water pipe and, well, it ain't there. They had the blueprints, but...so they called an old retired guy. He knew, said basically, 'We moved it because we hit ledge.'

They asked about noting it and he just shrugged his shoulders...'didn't think we had to'...

Amazing post!

I'm only half-way done reading this amazing post, great stuff. Wanted to quickly share a map I tried to make years ago in tracing the conduits of the Muddy River and Stoney Brook. This was the best tracing I could come up with: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1b6cxzrc2sjSqvztMoWv6oN-tlPc&ie...

And here's a video of someone walking up Goldsmith Brook: https://vimeo.com/37870115

What a great video!

Pairs with Adam's article perfectly. Delicious historical wonkiness plus vicarious video adventure equals an hour well-spent!

Thank you for sharing!

Your trace shows it close to

Your trace shows it close to the rear of Doyles, it used to be detectable , not sure now. It also fed Haffenreffer Brewery,and there was a pond at Roxbury Crossing where Station 10 was I think.

Great research

I read Mark Bulger's articles last year when I looking for background on the brooks. You have taken this to a whole new level. Terrific photos and maps. Thanks for writing this. I will go back and read it again (and again).

Interesting that as Stony Brook was being covered, the Muddy River was being designed by Olmsted.

Also interesting ...

Is that the city ignored the lesson of Stony Brook - if you're going to stick a stream in a tunnel, better make sure it's a damn big one - and so in 1996, we got a lot of rain and the Muddy River burst its banks where it entered a couple of conduits that were too small and flooded out the Green Line and knocked Kenmore station out for weeks. All the work the Army Corps of Engineers and contractors have done over the past few years was basically to keep that from happening again (in part by "daylighting" the river in front of Landmark Center).

Back to OG design

I have a book of Frederick Law Olmstead's projects and there many photos of the emerald necklace - one of which looks like a "new" picture of the recent day lighting that they performed on the muddy river by the Fens.

Honestly, it looks like they are going back to the original design - one hundred years later!

Muddy River II

work is almost finishing the planning stage. Stay tuned.

Muddy River

The section of the river near the Landmark Center used to be daylighted in the fifty's. The cause of the river flooding was the grating covering the tunnel entrance became clogged with tree branches and debris which caused the river to back up and overflow it's banks and flood the tracks then flow into Kenmore Station.

Crayfish used to thrive in the Muddy River near the Museum of Fine Arts just upriver from the Forsyth Gate.

Schools of Herring would come upriver to spawn in the spring.

This is really high quality

This is really high quality information. Can you think about putting this type of thing into some type of sidebar where people can find it in the future? I think this deserves more than just a single day's attention.

Hmm, good idea

Maybe I need a listing of the history-type stuff I've done ...

Yes.

Yes please.

You do interesting stuff, and having it accessible would be A Good Thing.

(Also, this was a really fascinating post. I just moved to Easton after living 14 years on Maplewood Street, so next time I'm up in the area, I'll have to check some of the specific places you mention out.)

A Brook in the City

The farmhouse lingers, though averse to square

With the new city street it has to wear

A number in. But what about the brook

That held the house as in an elbow-crook?

I ask as one who knew the brook, its strength

And impulse, having dipped a finger length

And made it leap my knuckle, having tossed

A flower to try its currents where they crossed.

The meadow grass could be cemented down

From growing under pavements of a town;

The apple trees be sent to hearth-stone flame.

Is water wood to serve a brook the same?

How else dispose of an immortal force

No longer needed? Staunch it at its source

With cinder loads dumped down? The brook was thrown

Deep in a sewer dungeon under stone

In fetid darkness still to live and run —

And all for nothing it had ever done

Except forget to go in fear perhaps.

No one would know except for ancient maps

That such a brook ran water. But I wonder

If from its being kept forever under,

The thoughts may not have risen that so keep

This new-built city from both work and sleep.

-Robert Frost

Stony Brook

Fascinating history and material.

When I was growing up in Hyde Park, we thought of Stony Brook as the name for the streams winding through the George Wright Golf Course. The brook flows from near the 18th green, passing through some backyards on West Street before re-entering the golf course, then skirting the 17th fairway and the 12th green before spilling into a little pond near the 13th tee. From the pond, there's another stream bed that leads into the Stony Brook Reservation. I remember as a kid hearing that the brook went all the way to Texas--surely a tall tale.

I lived on the hill overlooking the golf course, going back almost 60 years ago. At the time there was another little stream in a wooded area not far from our house (somewhere between Asheville and Lodge Hill roads).

One of William Pynchon's descendants was the novelist Thomas Pynchon. In "Gravity's Rainbow," there's a fantastical part set in Boston that involves a journey through the sewer system. Reading about the underground waterway here brought that back to the surface.

I wonder if it feeds into Turtle Pond

Or maybe Stony Brook directly? In either case, you could certain call it part of the Stony Brook system (I think there's yet another little stream that may come in via a culvert under Washington Street from West Roxbury).

Stony Brook reservation got

Stony Brook reservation got the name becuase it is the origin of Stony Brook. All the little streams that run through the area eventually do drain into the brook system. The main drain for the system is at the beginning of Enneking Pkwy, near Gordon ave.

1886 Man Made Global Warming?

Great to know that there were fluctuations in weather and climate in 1886, long before the influx of fossil fuels.

Further proof "man made Global Warming" is a fraud that made divorced Al Gore a billionaire in his coastal mansion. Apparently not too worried about "sea level rise."

Check out February 2017

Near zero temps and then high 70s. With tornadoes.

Not much ice/snow to melt, either. Too warm for that.

Notice the shift?

WARMER.

Blue Hill Observatory Data

Nice bullshit, grampa.

Now lets look at some actual data going back at least as far as this flooding incident - like, 50 years earlier.

July 2018 was one of the hottest on record. Most of the hottest on record since the 1880s have been recent:

BHO Warmest July Mean Temperature (24-hr adjusted mean), deg F (1885-2018):

1) 75.1 in 2010

2) 74.9 in 1952

3) 74.1 in 1994

74.1 in 2013

5) 74.0 in 2011

74.0 in 2016

7) 73.8 in 1999

8) 73.6 in 2018

9) 73.5 in 1949

10) 73.2 in 2012

Now lets look at how the temperature has been rising since 1880 or so, and with an inflection upward in the last 15 or so years (as in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2016, 2018 all being hot years ...):

Give your "clever" stupidity act a rest. It isn't clever, and it is stupid.

This is indeed an example of weather

Not climate. Dumbass.

Climate (noun)

the composite or generally prevailing weather conditions of a region, as temperature, air pressure, humidity, precipitation, sunshine, cloudiness, and winds, throughout the year, averaged over a series of years.

(emphasized the important part for you)

It might have been climate change related

Humans were pumping a lot of CO2 into the atmosphere from the dawn of the 19th century onward.

There is scientific evidence that it was changing the climate even then: https://www.carbonbrief.org/scientists-clarify-starting-point-for-human-...

A round of applause, everybody!

Wow, you discovered it sometimes rained a lot in the 19th century. Where would you like your gold star?

In any case, no further need to discuss global warming here; others have made the point that you don't really have a point, at least in this context.

So no replies necessary to your comment; I'll just delete them as, well, pointless.

Breweries

Thanks, Adam. This adds more detail to a lot of what I learned at Brew at the Zoo this weekend, which included a lecture on "Lost Breweries of JP and Roxbury."

For those interested in that part of the story: https://www.jphs.org/victorian-era/bostons-lost-breweries.html

Runs under my back yard

Off Wyvern St. In fact it is the border between Rozzie and JP’s Woodbourne area.

Great history!

A good way to follow the route of the Stony Brook Conduit through Roslindale, at least east of Hyde Park Ave., is on the City of Boston assessment maps, where the corridor is marked as Stony Brook Reservation. You can view the corridor pretty clearly, though it is not labelled, on the Boston Zoning map at http://maps.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/zoningviewer/

The Boston Water and Sewer Department owns much, but not all of the surface over the conduit; some of it has been sold to abutters with a conservation restriction.

This is great!

Thanks for putting this together.

What a fantastic article, with a fantastic amount of research.

I read it with much interest, and found it fascinating. Thanks for all the research, adam.

@_@

This is amazing. I vaguely remember that tunnel getting filled in but I had no idea of the history of the waterways. Mad props Adam!!

Under Boston

This is the best thing I've read in a long while. Thanks!

I learned about 30 years ago about the Stony Brook conduit running right next to the basement at Doyles. It's great learning about all these other details. Now I feel like exploring.

Daylighting

Great stuff! Just imagine daylighting the Stony Brook as it courses along Amory Street!

https://urbanomnibus.net/2013/11/daylighting-rivers-in-search-of-hidden-...

http://273aiv293ycr20z8q53p7o04-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploa...

We lived on Hubbard Street off the Southwest Corridor from 1993 until 2008. We didn't know about the existence of the Stony Brook until 1996 (I believe) when rains overwhelmed the storm drainage into the brook and our basement flooded.

https://stonybrookinboston

https://stonybrookinboston.blogspot.com/

Water rights or hydro

I'm curious - if some business wanted to use this water for some reason and they were adjacent to the tunnel, I wonder if they'd be allowed to tap into it?

Similarly, it would think that at a certain point fairly far into the system, there is probably not much debris - could a turbine be installed to capture hydroelectric energy?

Stony Brook thru Roslindale

I always thought the submerged Stony Brook came down from Turtle Pond by way of Washington St towards Roslindale Village. I once heard that the folks at Trethewey Bros (at corner of Kittredge and Wash St ) could hear the stream beneath their floor boards on very rainy days. I believed it because we live on Cliftondale St (off Albano St) at the top before it goes down hill toward Kittredge and many of the homes around here get water in their basements, some quite a bit (incl ours) when it rains alot. How could we get water in our basements living at the top of a hill? I summed it up to a tributary of the Stony Brook too close to our foundations. I guess this story posted by Adam dispels that myth!

Fantastic Read.

Thank you so much, you solved at least 3 "What are those things?" mysteries for me. What a great read!

Thanks!

Thanks! I know I used to think the Charlesgate gatehouse (the one you see getting onto Storrow from the Fenway) was an abandoned comfort station.